It’s easy these days (and a little cheap) to rail against the old school classroom as a teacher-centric, autocratic learning environment. We hear this often; product marketers, overzealous reformers, and technothusiasts seem to express the sentiment that old school teaching is irrelevant in a high-tech world, or that if you’re not with what’s up-and-coming, you’re out to lunch, and you certainly can’t be providing a good educational experience for kids.

This is the twelfth of fourteen posts in a series about the role of cognitive science in education.

To have future posts delivered to your inbox, choose "subscribe" from the bar on the right side of the screen.

Introduction:

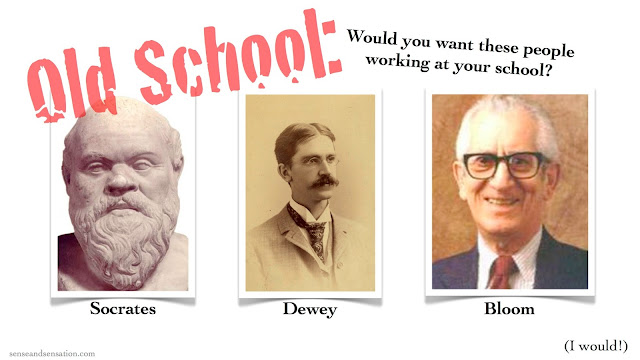

But 2400 years ago, the Socratic method promoted discovery through asking questions, and we’ve explored how it does, indeed, provide a rich, cognitive experience. We continue to hold this kind of teaching in high esteem.

And 100 years ago, Dewey codified the ideals of experiential education, arguing that primary experience is essential to constructing understanding. This is good teaching; it is a model of rich encoding, of multi-sensory experience. In fact, at over a hundred years old, it remains a foundational element of the immersive experiences that choruses of reformers advocate for today.

And 50 years ago, Bloom, of course, reset our understanding of educational objectives in a way that promoted active student engagement. Movement through Bloom's taxonomy (and its revisions) requires rich, immersive work.

Because of these and many other examples, I think it’s important not to villainize the term “old school,” because history--the philosophy and practice from the past--history is what we learn from. It is flush with wisdom, and we are foolish if we ignore it or overlook it.

Instead of talking, then, about old school and new school teaching, let’s differentiate between good teaching, which stimulates thought and activity, and bad teaching, which stifles it.

And this is a key distinction, because good teaching isn’t always flashy. It doesn’t require anything fancy, and it doesn’t have to be expensive. (Though, sometimes fancy and expensive tools can be helpful.) Mostly, it requires thoughtfulness. It requires organized, thorough, and deliberate preparation. It requires empathy, and a degree of responsiveness in the moment.

Good teaching comes from a place that understands how and what students think and feel. This doesn’t have to mean a deep understanding of cognitive science--strong intuition and emotional intelligence can go about as far anything towards reading the thoughts and feelings of a room--but a systems approach to thinking certainly helps inform our work as educators. Since good, cognitive learning is an essential aim of teaching, understanding the mechanics of thought and memory provide a hearty, sensible foundation for our work. Stimulating, thought-provoking, action-inducing teaching is good teaching, however old it may be.

Seeing new school and old school in this way--in the context of good school--is the point of this post. And it is close to a key insight that this whole series of posts aims to address: an understanding of what is new in relation to what is old. In this case, this means one thing in particular: the relationship between the cognitive science of learning and the historical work of teaching.

Certainly, another context for understanding the relationship between old and new is technology. And this will come next, in the penultimate installation: Technology, the Brain, and Teaching.

This is the twelfth of fourteen posts in a series about the role of cognitive science in education.

To have future posts delivered to your inbox, choose "subscribe" from the bar on the right side of the screen.

Introduction:

- Cognitive Science: The Next Education Revolution (Part 1 of 14)

- A Cognitive Model for Educators: Attention, Encoding, Storage, Retrieval (Part 2 of 14)

- Attention: the "Holy Grail" of Learning (Part 3 of 14)

- Encoding: How to Make Memories Stick (Part 4 of 14)

- (Interlude) Long Term Memory and Working Memory (Part 5 of 14)

- Storage I: How Memory Works - Redux (Part 6 of 14)

- Storage II: Sleep and Memory (Part 7 of 14)

- Retrieval: Getting and Forgetting (Part 8 of 14)

- Cognitive Design: Essential Questions for Educators (Part 9 of 14)

- Character and Success... and the Cognitive Model (Part 10 of 14)

- Towards a Unification of Pedagogies (Part 11 of 14)

- Why Old School and New School Aren't in Conflict (Part 12 of 14)

- Technology, The Brain, and Teaching (Part 13 of 14)

Comments

Post a Comment